The Lion on the Line.

From the series: Tales from the Asylum

Her living space: corrugated iron roof, a mosaic woven wall piece hanging in the background, some scattered cushions dotted about. Areas divided into kitchen, bed, and sitting room — spacious, it looked comfortable. Outside was the African Savannah. Inside, the animals still found their way in. A Belgian Malinois with huge pricked grey-blue ears jumped up and stared at me through the distance, and squirrels skated along the rafters.

“Signal’s bad in here today,” she said, between the freezes and flickers.

We rejoined outside.

We were on a vast plain. An almost treeless expanse of pale grass stretching out to the far horizon. Heat shimmer. Her eyes darting left and right, quick and sharp.

“You okay?” I asked.

“Fine,” she said, calm as stone.

“There’s a man-eater about,” she looked at me with serious eyes and said. “Took one of the villagers yesterday.”

She lifted her hand. A revolver.

“Don’t worry though. I know how to use this.”

She was a park ranger in Africa. Carrying a sidearm was routine. Poachers. Lions. Whatever came. The gun sat easy in her grip, like it belonged there.

On my side: a cup of tea, rain tapping gently on the window.

On hers: hot wind, a distant horizon, a revolver.

The camera angle gave me a the scene behind her — the blind spot she couldn’t see.

“Well, don't worry, I’ve got your back,” I said. And we laughed.

And I meant it. My job, in that moment, was lookout.

She didn’t keep it spare. She let it pour. Twenty minutes without a break.

Childhood marked by drink and chaos. Parents who left dents she still carried. Ballet protégé — discipline, international success, beauty, freedom, escape — and the cost carved into her body and mind. One moment tearful, the next alight, describing the work she loved now. Then swinging again, into the mess of her relationships — colleagues and government impossible, partner volatile, everything all tangled up.

It came in a rush, a single exhale that seemed to empty her out.

Then the screen froze.

For long seconds, I stared at my own face in the corner mirror of the call.

Rain tapping the glass behind me.

On her side, the Savannah and the story were gone.

When she came back, she was already scanning the horizon again, revolver ready.

“You’re back,” she said, as if I’d stepped out of the room and in again.

“Still here,” I said.

She set the revolver on a table, half in view.

“They don’t usually hang around once they’ve eaten,” she said at last.

“But we’ll have to go and get it. If it’s an old lion, it’ll be back for more, an easy meal it won't forget.” she said solemnly.

She walked back inside. Tin roof ticking. The Malinois at her side.

We wrapped with a few minutes of tidying up work.

“Thanks,” she said. “For watching out.”

“Any time,” I said. And meant it.

After we ended the call, what lingered wasn’t the lion.

It was her calm — and the contrast with everything she’d just spilled.

Twenty minutes of her life, unfiltered: an alcoholic father who couldn’t stay faithful, the wreckage he left, ballet as both escape and discipline, the urgency, the highs and the cost. Then the partners and colleagues, each a knot of difficult love. She swung between tears and fire as she spoke, alive in the telling.

And when it stopped, she sat perfectly still, like nothing had been said.

And then, when the call reset, and she stood out there scanning the horizon, revolver steady in hand, it was like another part of her entirely.

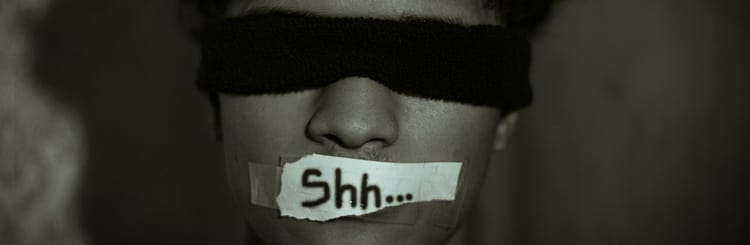

That’s the split I keep seeing in clients with trauma histories.

Drawn toward danger — diving, climbing, frontline work, success at all costs — and where risk sharpens them.

In peril, they’re calm. Efficient. Precise.

But a partner’s anger, a hint of conflict or the slow injuries of closeness — those undo them.

Two worlds.

Chaos in intimacy.

Control in mortal threat.

That day on screen, she carried both.

A woman steady with a revolver,

and a life that shook when the gun was out of sight.

Author’s Note

This essay is part of Tales from the Asylum, a series written from inside Britain’s psychiatric system. These are composite accounts, anonymised to protect privacy, drawn from decades of frontline practice.

Member discussion