The Chemistry of Control.

He’d been inside secure environments for almost ten of his 26 years. A locked unit, routines set in stone, his life paused while everything outside carried on. When I met him, he was edging towards release. It was fragile. One slip, one hint of trouble, and the gate would slam again.

He loved numbers. Proud in his ability to reel off prime sequences without blinking. He loved cycling too — long rides until his legs ached and his laughter spent, the kind of rhythm that gave him space in his head. He was cautious at first, wary of professionals, wary of me, but once trust was there, he opened. And he was warm. Funny in a sly way that made you double-take.

I knew he wasn’t taking his tablets. I knew he was drinking a little. I didn’t care. He was steady enough as far as I was concerned, and I wasn’t about to jeopardise his chance at freedom. I was a locum, passing through, only feigning loyalty to the team, and as always, no interest in playing policeman. My role, as I saw it, was to help him out of there, not pull him back in.

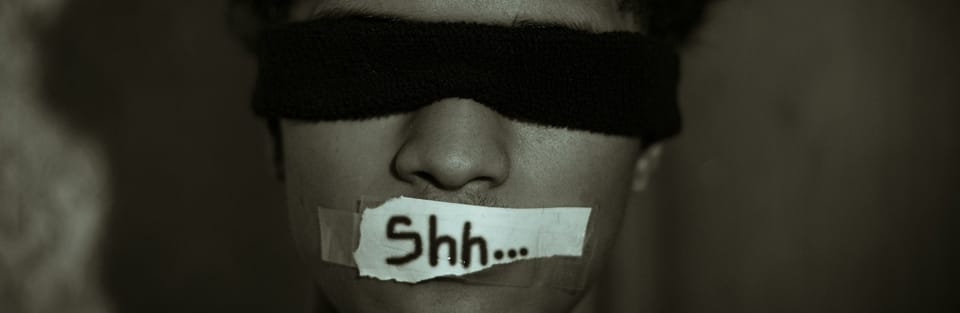

So I kept my mouth shut. I rode bikes with him instead. For those few hours on the road, he looked free, I felt it with him.

The clinic went on around him. The blood tests, the monthly reviews, the little paper cups. He’d sit there, answer the same blunt questions.

“Are you hearing voices?”

“Taking your meds?”

“Good.”

The notes filled themselves. Stable. Progressing well.

The record said he was doing fine. I never said a word. Because if anyone knew what I knew, they’d clamp down hard. No release, no bike rides, no chance to step outside and feel air that wasn’t regulated.

Ten years is a long time to wait for your life to start again. My job wasn’t to stand in his way.

Author’s Note

This essay is part of Tales from the Asylum, a series written from inside Britain’s psychiatric system. These are composite accounts, anonymised to protect privacy, drawn from decades of frontline practice.

Member discussion