The Beast of the Bogs

The coach jolted south, cigarette smoke leaking through cracked windows, patients slumped in the seats. Roman—placid, huge, unreadable—sat with a nurse welded to his side. The rest of us scanned faces like prison guards. Every few minutes, the same nagging thought: Where is he? Where is he?

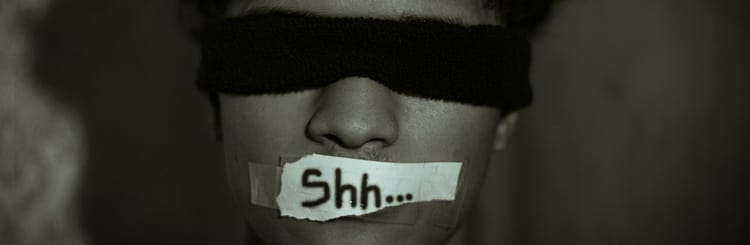

He never twitched. Never raised his voice. Just sat there like a teddy bear drugged up to the max on a coctail of anti psychotic medication. Hard to believe he’d earned his nickname—The Beast of the Bogs.

Early nineties. London’s inner-city psychiatric wards had been unofficially rebranded as crisis units, the “community care” experiment after the large old asylums shut down. Not havens. Battery farms of chaos.

Corridors stank of lunch, tobacco and floor cleaner. Medication trolleys wicked wheels rattled like supermarket cages. Fire alarms screeched half a dozen times a day—sometimes false, sometimes a burning bin. The soundtrack was doors banging, shouts flaring from side rooms, the occasional sobbing collapse in a corner chair. Constant simmering danger, absorbed as background noise.

And into this walked Roman.

Twenties. Afro-Caribbean heritage. East London poverty written through him. Barely spoke. A muttered “Yes.” “No.” That was it. He padded the corridors like a big bear, docile but unreadable. Something about him prickled the hairs on your arms. Everyone felt it.

The meds were maxed. Not titrated, just hammered in—because the ward was unlocked and understaffed.

We knew his story, told the doctors: this isn’t safe. He needs secure care. They shrugged. “He hasn’t done anything here.” Secure beds were blocked, some ringfenced for consultants’ private referrals. You could smell the corruption: empire-builders doubling up as directors of private clinics, patients siphoned off there to ease waiting lists—for a fee. Roman wasn’t priority. He was just another body dumped on an open ward.

Then came the bright idea: a day trip. Brighton, fish and chips, sea air. And Roman was coming.

Madness. We planned one-to-one cover, but staffing was thin. A nurse stuck next to him couldn’t rotate out. Even a psychiatrist tagged along—which told you everything.

The trip passed without incident. But it felt like walking a tiger on string. Everyone’s eyes tracked him. He just sat there, knees jammed against the seat, blinking slow, picture of compliance.

Back on the ward the tension rose. The building was made for disappearances—long corridors, blind corners, toilets tucked away.

One shift he was missing for an hour. Then came the news: he’d cornered a nurse in a side toilet and raped her.

The shock was sharp but not surprising. Everyone knew something was coming, even if no one said it aloud. Horror, yes. But also inevitability. He’d been left to simmer until the boil spilled.

Afterwards: stunned faces. A couple of staff quit. Agency nurses filled the gaps. The rest swallowed it and carried on. Suppression is survival. You blunt your horror and keep working. That’s burnout—not weak resilience, but forced numbness in a system designed to break you.

The official line: Roman had finally “done something,” so now he could be transferred to secure care. As if the assault was paperwork to free a bed.

The truth was simpler and crueller: the system knew the risk and tolerated it. Beds rationed, corruption thriving, coercion dressed as care. Roman wasn’t a surprise. He was inevitability disguised as accident.

I still picture him on that coach, knees jammed against the seat in front. Breathing like he belonged there. The bus held its breath with him: Where is he? Where is he?

The beast wasn’t the man. It was the system that waved him through.

Author’s Note

This essay is part of Tales from the Asylum, a series written from inside Britain’s psychiatric system. These are composite accounts, anonymised to protect privacy, drawn from decades of frontline practice.

Member discussion